Three years ago – a year into my own personal learning journey with ustwo – I was chatting with one of our developers about how we could improve communication between developers and designers. It was during this conversation that I was first introduced to Behaviour Driven Development (BDD).

There are countless books, resources and websites out there to help you understand BDD but it’s easy to look at those materials, as I initially did three years ago, and assume it’s not relevant for designers. What use could a practice aimed at helping developers and QAs run automated tests possibly have for a designer?

Well, I’m glad you asked.

For me, BDD is primarily a tool for collaboration.

Collaboration is at the centre of ustwo’s ways of working. In practice, that means that designers, developers and product owners work together as closely as possible, at all stages of the product delivery process, in order to achieve a goal. Whatever the context we’re working in, that goal is always underscored by a commitment to do the best work we can and to build products that users love.

While working together and with our clients, we make sure we pick the tools, processes and practices that best suit our projects and teams. In reality, this means we’re continuously learning and constantly experimenting.

BDD helps developers and designers combine their thinking and tackle problems together, from the very first stages of a project. It invites the team to get together and allows each discipline to bring their unique perspective to the table.

So what exactly is BDD?

Imagine your team is midway through implementing a feature in an app, when someone says, ‘What happens here if the user’s account gets suspended?’

Ouch! We hadn’t thought of that – how could there have possibly been any more use cases out there? It often feels like you must have covered everything between the stories, sketches, prototypes, flow diagrams and hours of talking to the team.

Well, it happens. The complex nature of the products we build means we can’t possibly think of everything at the start of the project. That's why BDD is so valuable. It helps the team spot and document these scenarios ahead of time – before any code is written – because everyone is involved. Each person attempting to approach a solution from their own unique angle, through their own lens.

How does it work?

As previously mentioned, a big part of BDD is collaboration. Nothing in BDD epitomises collaboration as much as the Three Amigos session.

Three Amigos is the process that helps you see potential scenarios and behaviours and think about them, whilst BDD is the process that stops you coding before you've thought of these things. The ‘three’ in Three Amigos refers to the different stakeholders present in the session - typically a Product Owner, a Developer, and a Tester. However, you don’t have to limit yourself to these three – at ustwo we believe there should always be a Designer in the room as well. It's important that everyone, each with their different backgrounds, adds their input. No one person has all the answers!

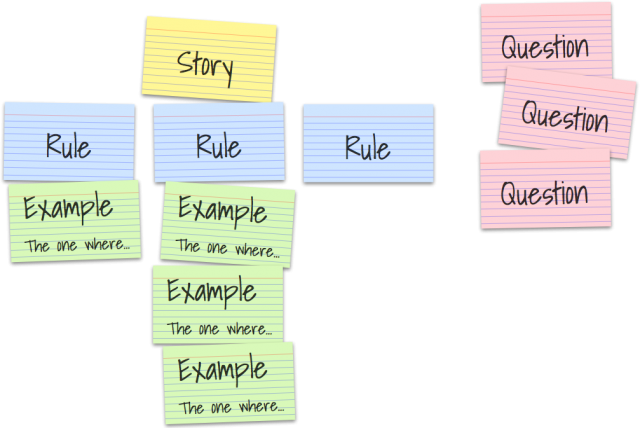

Each Three Amigos session begins with a practice called Example Mapping. The focus of this part of the session is for the team to get together and break down one of the user stories from the backlog into smaller examples. These can later be used to help write our BDD scenarios.

Essentially, Example Mapping involves pulling out each rule or acceptance criteria of a particular story, and then writing down one or more clear examples that show that rule in practice. Any questions we have about where the story needs more clarity are also captured. You can read more about this process in this introduction to Example Mapping.

The exercise will help the team to thoroughly comprehend the scope of the problem they are facing, before building each feature. We tend to do this before jumping into sketching. It allows everyone to share their knowledge and bring their viewpoint to the table. This collective input is valuable for everyone – it means a designer is not expected to come up with every single way a product behaves and others in the team can more fully engage in the early stages of product development.

In my experience, Example Mapping is especially helpful when attempting to write your BDD scenarios for the first time. I've been in sessions where we spend over an hour discussing what the scenarios are for a particular user story and attempting to write these down. If you make sure that this preparation exercise has been done well, then you’ll spend less time trying to come up with BDD scenarios and you may even find you have a few new user stories that can go into the backlog for later. The focus of the team then becomes how to implement the new feature and its behaviours – rather than trying to tackle a large, complex, and potentially ambiguous story all in one go.

The Source of Truth

After Example Mapping, we move on to documenting our features and scenarios – or creating, as my team calls it, ‘the source of truth’. For each feature in our product, we create a shared document that contains all of the possible scenarios.

Perhaps, you have worked in an organisation where you spend hours designing screens in order to communicate how the product behaves. However, through using BDD as part of our ways of working – we are all in the same room, discussing the same scenarios and can more quickly align on what behaviours the product should exhibit and afford. Once we have reached consensus, we can then document the expected behaviour quickly, in a way that all stakeholders can understand.

BDD in Action

Let me show you an example. Imagine I’m on a team working to build a new online shopping app. One of our highest priority user stories is as follows:

“As a customer, I want to only see items that are in stock, so that I don’t waste time viewing items I can’t buy.”

Chances are you’ve seen something like this before – at some point, we captured a high-level user story about something our users want to achieve. It’s fair to say there’s not much detail here, and we certainly couldn’t start development right away, but this short sentence acts as a good central focus and starting point.

In the Example Mapping exercise that starts the Three Amigos, we pull out each piece of acceptance criteria:

- If an item is in stock the item should be visible

- If an item is out of stock the item should not be visible

These become our Rules and for each rule, we come up with some obvious examples:

- “The one where there are a number of items matching my search that are in stock”

- “The one where I search for a specific item but it’s out of stock”.

This is referred to as the ‘Friends episode naming convention’.

As a designer, you might be thinking, “wouldn’t it be helpful to show items that have very low stock levels so I don’t waste time hesitating and potentially miss out?”. In the Three Amigos, we can discuss this openly, and maybe even come up with a new rule and another example:

- If there is only 1 of the item in stock, that item should be flagged as the last one

- “The one where the item is in stock but there’s only one left”

These examples have got everyone talking about and understanding the out of stock user story and we now have something against which to write our BDD scenarios. We might not write these there and then, but one example BDD scenario might look like this:

Given there is only one blue scarf in stock

When I search for “blue scarf”

Then I should see a blue scarf for sale

And I should be informed that it’s the last one left

We write our Scenario in a syntax known as Gherkin. Gherkin has a few strict but simple rules, the most obvious is that each step in the scenario must start with either Given, When, Then, And or But. Many scenarios combine to create a Feature.

Documenting even the most complex features in this way allows you to leave the room knowing that every single discipline has a clear idea of how they should proceed with their work. If you’re a Product Owner, you’ll hopefully leave assured that your team has understood the goal of the feature. If you’re a designer, you know that devs are not going to wait for you to mock up each screen in every state before starting to code. They can get on and create the technical foundation of the specific feature you have agreed on. Designers can then get on with preparing for the sketching session, creating prototypes to explain specific details such as transitions, or preparing for user research sessions.

This doesn't mean that this ‘source of truth’ – the document comprising of the teams shared ideas – can never change. You might do user research and realise that some of your assumptions were wrong. In that case, you could go back and tweak some of your scenarios. All it means is that people working together will always know what is the latest ‘source of truth’. Make sure you talk together and continue learning and sharing as you go.

Getting started with BDD

Maybe this all sounds great but if you're unsure of how to make the next step, here are some practical steps designers can take to get involved in, or introduce, BDD.

If you’re in a company already practicing BDD, invite yourself to a Three Amigos session. Again remember, this isn’t just for three people. If you’re not practicing BDD as a company, you can introduce it: start by reading The Cucumber Book – the first few chapters should be enough to get the gist – then schedule a Three Amigos session. The discussion will be useful even if you don’t take your scenarios any further. I’ve found that even co-location isn't always necessary – I’ve worked with teams that used a video call and a Google Doc as a way for remote team members to participate and share knowledge. If you are in a meeting together, make sure that everyone is participating and it’s not just left to one person.

To recap, BDD as a process helps to remove ambiguities and uncertainties, allowing you and your team to have a shared understanding of the product goals. If the opportunity is there for everyone to write scenarios together and contribute in documenting their ideas then you can all stay firmly on the same page.

Designers can be wary of BDD and scenarios because they think it’s too technical – but that’s not the case. It’s really just about inviting designers to be involved before any code is written and allowing developers to have clear requirements that can be automated through tests at an earlier stage. I hope this post dispels some of that technical mystique and encourages you to give it a go!