We've all heard about how design is going to save us. Super clever start-ups are going to disrupt old-world thinking and innovent (thanks Jack Donaghy!) solutions to fundamental human problems. We'll live better measured, data-producing lives that feed back into smarter and more convenient systems. We'll be so fulfilled! Design cares! I can't wait for the future!

OK, so cynicism is amusing for about a minute. Ultimately it's just idealism gone sour. Of course I need to believe what I do makes people's lives better. If people don't feel a service or experience is making something better for them, they won't bother using it. That's what makes them ‘users.’

As interaction designers, we work to understand what ‘better’ means for businesses, developers and ultimately users. We try to create better experiences, better interactions, better propositions, better solutions.

I'm also interested in making my day-to-day life better and exploring what it means to be a better human being. I've experimented with different approaches and experience varying levels of success failure. I've evolved a set of values that have definitely made my life better.

Something has been nagging at me: how come my version of "better" is so different from the solutions or apps I design to make people's live "better"?

Perhaps these contexts aren't comparable. My experience likely nothing has to do with what a group of users might need, right? But users are people too. And I was curious to compare what the values behind these two versions of "better" are.

Better technology for better humans

Digital and technology-driven solutions have a strong bias about what's better. We tend to assume it's simply better to:

- Get more information to more people, and

- Make every process more efficient and convenient

The drive to constantly optimise comes from stunning technological breakthroughs. As these limits fall away, our human ones do as well. It's pretty magical to be able to translate a conversation on the fly or orient yourself in a foreign landscape.

That drive to transcend limits is what underlies our current cultural beliefs about technology. Tech-driven solution thrive on the assumptions that:

- Progress is inevitable

- Technology is always the best solution

- Everything is measurable

These are powerful and insidious beliefs. Dr. Galloway describes these beautifully in her article on ubiquitous computing. Go read it. I'll wait.

Done? Now let's look at what 'better' means:

bet·ter /ˈbetər/

- Greater in excellence or higher in quality.

- More useful, suitable, or desirable.

- More highly skilled or adept.

- Greater or larger.

You get the idea. Better is more of what is good.

If "better" means more convenient services, increased efficiency and more data faster, then "good" must equal convenience, efficiency, measurability and speed.

Experiments in being a better human

Back to my experiments. I figured a better day-to-day meant better habits. It seemed simple enough. I want to be healthier? I should eat more of x and less of y. I want to spend more time working on a personal project? I should be more efficient with how I use my time.

I read endless productivity blogs, I consulted with friends, I experimented. I tracked what I ate, logged how I used my time, scheduled around core commitments, made lists, made spreadsheets and downloaded more productivity apps. It worked really well… for a time. I'd exercise more, eat better, see who I wanted and get more done.

But I'd never be satisfied. I could always do better, do more, use my time better. If I slipped up it would feel like a personal failure. And if I did well better was always still out of reach. I was more productive but less resilient. When something changed or I fell sick—basically when life happened—I felt pressure to get back on top of it all. And I'd eventually lose touch with why I was doing it in the first place.

The problem? The means became the end. Tracking became a value rather than a tool, efficiency a virtue rather than an approach. Being more productive could help make time for what I cared about, but it didn't add more meaning to my life in itself.

My values are not to be more productive. My values are better lived out if I use my time productively. Big difference.

Wait, what's human?

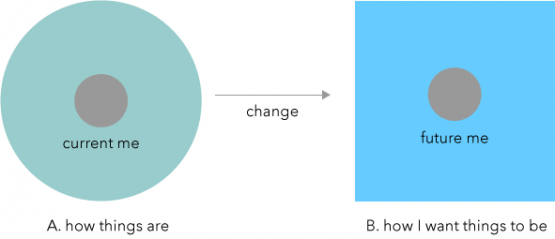

It's hard to be a better human when being human seems to involve constant dissatisfaction. It's why we want to make things better. And that involves changing something. Usually changing how things are to how we'd like them to be.

All the techniques I used were basically to change A to B in the belief it would make my life better. Sometimes you can change things to suit you. But when you can't, what do you do?

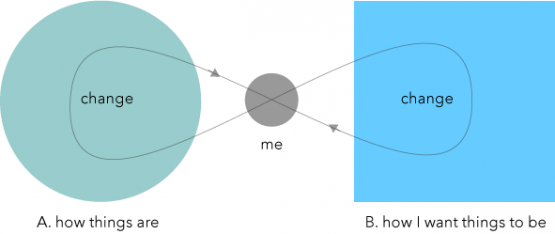

Mindfulness practice helped me make space to stop, slow down and try to see things as they are. I realised "better" isn't a goal, it's an outcome or practice.

When I was in touch with the underlying desire for making my life better, I realised it was quite simple: I wanted to live a meaningful life where I stayed in touch with a sense of purpose.

As in all design processes, changing the frame of the problem opened up different solutions. I didn't have to be attached to any one tool and it could change day to day. It could mean keeping a schedule one day or tossing it out another.

It forced me to trust my sense of purpose rather than my tools. I tried to do less and listen more. Choosing not to give in to FOMO (fear of missing out, now optimised by Facebook), to read and see everything and meet everyone creates space for life to actually happen.

And better happened when I used those tools in service of making this a two-way conversation:

We've a bit of an obsession with changing the world. It's a chaotic place and that's what our tools help us deal with. But sometimes it's about changing the world, other times it's about allowing the world to change you.

Interestingly, the word 'better' has a more ancient etymology. The old English *bot* meant "help, relief, advantage; atonement," or "remedy, reparation." It's a very different idea of better. It's not about fixing or adding anything.

Balancing listening and doing helps heal the rift between things as they are and things as I want them to be. That's how better emerged for me.

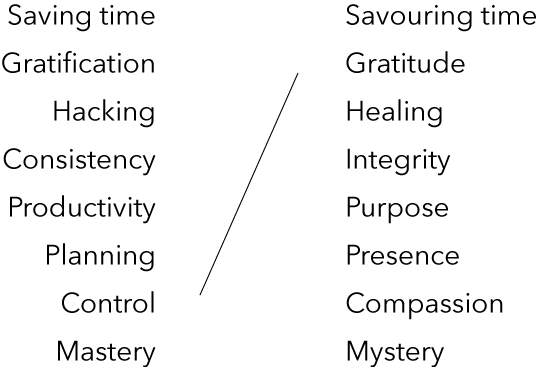

Comparing the values I work from and the values I live by now looks a bit like this:

Reframing desire

Perhaps these values apply to different aspects of our lives and it's fine that they're separate. But we only ever design for one set of values and we easily fall into the trap of confusing the means with the end.

Our personas are 'time-poor' and 'gadget hungry', they want a more 'convenient experience' that also happens to feel 'tailored and personalised'. Is that really what they want? When we see human desires through the lens of technological solutions, we'll only see problems we know how to design for.

It may be those desires are perfectly appropriate to the context we're designing for—a banking application should just be quicker, more accurate and offer more control.

What would happen though if we were to shift the frame and design for a different set of desires? What if we were to design for the underlying desires, maybe one where money is in service to one's values and way of living?

Making things more convenient and efficient is great. It can also help make space for deeper commitments to better living. But it's important not to confuse the tool and the problem, or the effect and the outcome. It's when solution becomes prescriptive that the balance has tipped, when we rationalise new behaviours and squeeze human experience to fit our systems.

Helping someone access more information quicker doesn't mean we "fixed" the problem of them feeling closer to someone. And if that's not the problem we're addressing, let's not pretend it is. As long as we remember the difference there's room to design many more experiences of "better."