Juan Cabrera, ustwo Tech Principal, doesn’t leave his appetite for tinkering with tech ideas behind at the office. “Even at home, I’m always thinking way out there,” he says. Recently, he asked himself: “What would it be like to talk to a digital clone of someone you love?” So he created a highly realistic digital avatar of his teenager, Amanda, which became a family collaboration: Amanda, who wants to go to art school, lent their visual and creative skills to fine-tune their avatar’s appearance, and even their stuffed animal “Turkey” served as a 3D scanning test subject!

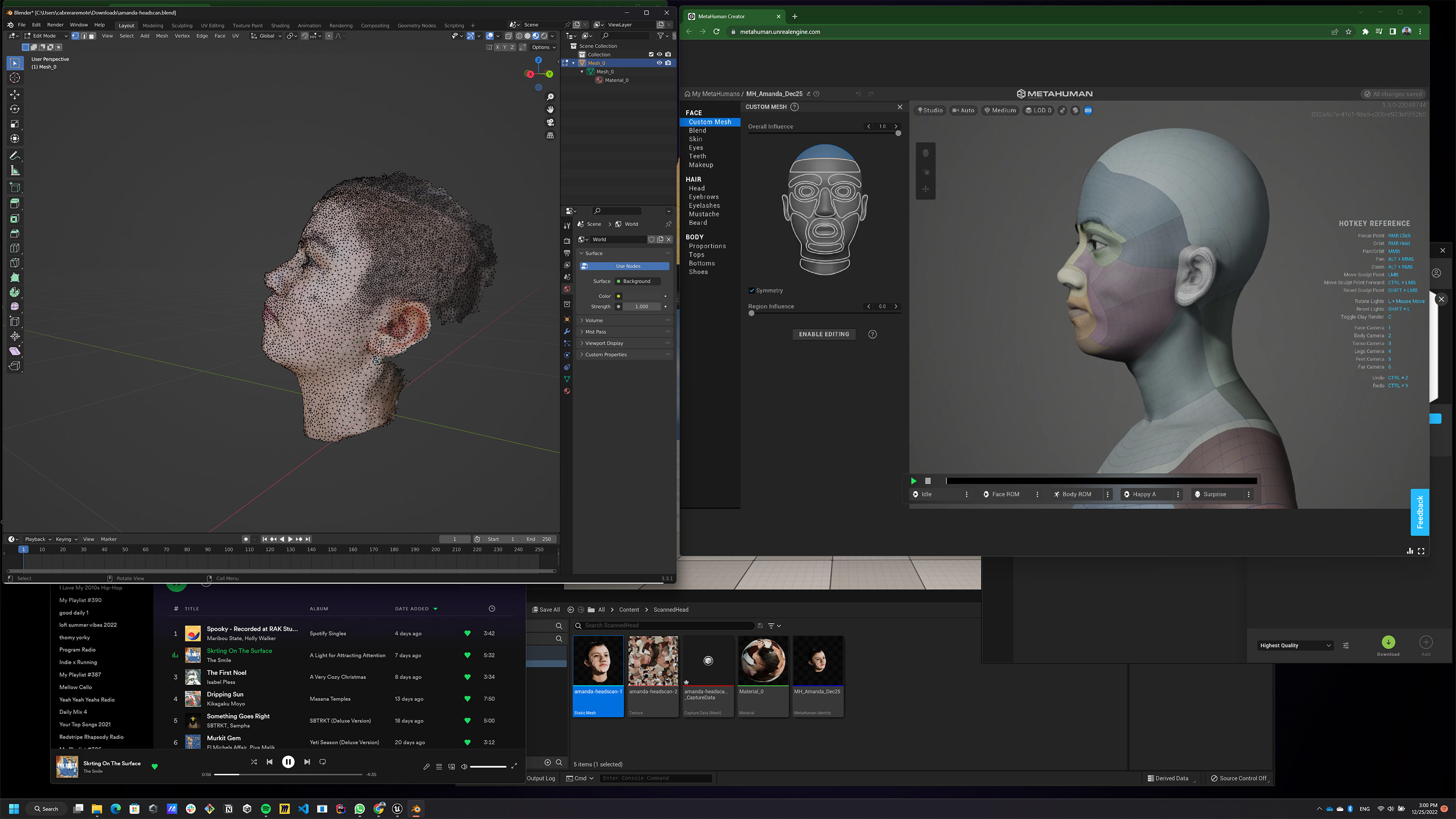

To create the digital Amanda, Cabrera used Unreal Engine’s MetaHuman programme, 3D scanning their face and finessing the visual details; the LinkFace app to record Amanda’s voice; and ElevenLabs for voice cloning with emotion. It took less than a week’s time to create the project’s current iteration.

We chatted with the dynamic duo about the process of creating this MetaHuman, Amanda’s reaction to seeing themself as an avatar, and where the project might go next. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Victoria Stapley-Brown: What’s unique about this project - what were you trying to accomplish with this technology?

Juan Cabrera: For me, it is almost a thought experiment. I had the idea in my head, but I wanted to see how it could feel to talk to a digital clone of someone you love.

Why did you decide to experiment on this project with Amanda and not someone else?

JC: With this kind of experiment people might get weirded out, you know, “Can I clone you, like a digital version?” I think I have very few people I can talk about weird stuff with. Amanda’s one of them. So I think it was number one, that I felt like I didn’t have to explain too much because they will get it. And the other one is the convenience of course, we live together, so it’s easier to scan Amanda’s head and record the audio and all of that.

Amanda Cabrera: Also as a kid, I think you’re more interested in seeing yourself as a digital clone. Younger kids are more exposed to video games, and seeing yourself as a character can be very thrilling. A big thing is video games for a lot of people, and that somewhat overlaps as a digital version of yourself. And many times in games, you’re trying to create a character that represents you, and I think this [project] was interesting, because many times you don’t get the full example that you want of yourself. I feel like also young minds are more interested in things like this – maybe not many people are exposed to it, but they’re interested in it, maybe, than older minds.

There’s the avatar that’s trying to be a digital version of you as you are, and then there’s being a person that you want to be. Did you want the MetaHuman to be as much like you as possible, or were you interested in making little tweaks?

AC: I was interested in seeing how realistic it could be, because I know technology is evolving rapidly: how real can this AI be to me? With my voice, with the muscles in my face, how can it be me? –

JC: The dye in your hair –

AC: Yes, my dyed hair - all the little things that fascinated me in how it was manufactured to be a me that isn’t me.

JC: Something really interesting that I found out is on Unreal Engine, which provides you with this tool to create the MetaHumans, you have two options: you can start from scratch, like from a [template], but the other way, which I did with Amanda, was to do a scan of Amanda’s head, and we did that with many people at the studio. So when you start making the MetaHuman, at least you start with the right shape, but still I was like, “Damn, I can’t get it right!” And then, I asked Amanda, “Can you give me a hand?” Amanda’s a lot more visual than me, so it was easier for Amanda to get it just right. There are so many factors: there are 43 muscles in the face, so what to move, and what to stretch, what to make bigger or smaller. I think for some reason even though you [Amanda] never used that app, it was easier for you to feel more comfortable [working with it], probably because of your constant exposure to emerging tech and because you’ve got a highly visual brain and can see things most people can’t. I think being a digital native is a factor – but not the biggest one.

AC: It wasn’t just, “Let’s see how well this can go”, it was “Have fun in the process as well”, which I think is a big part. We scanned my face but we also scanned our stuffed animal “Turkey” as well [Juan laughs]. It was a fun collaboration.

Juan, you said Amanda went in and touched up stuff; Amanda, what were you actually manipulating in terms of you picking out stuff, complementing your dad’s process of working?

AC: I like to draw and I want to go to an art school, so it was very fun for me to see all these nitpicky things that maybe the eye of an engineer won’t see. We also did a scan of my dad, and when we were doing that one, there’s a lot of things like – it looks really close, but it also looks nothing like you at the same time, because of certain details.

JC: It’s that 1% that makes you look like you, so it’s weird.

AC: So I think this has to be something that you work on with someone, because there’s so many things that one “type” of eye won’t see. And also older mind and younger mind, how we see different things, and also playing around with it to see what works best.

How did you feel when your Dad was like, “I want to make a digital version of you”?

AC: I was really interested in what he meant by that, because it wasn’t something that I’d seen before – I’d heard of it, but I’d never actually seen it. And I was also intrigued by seeing the whole process. I was a bit sceptical. I didn’t think it was going to work out, no offence to Dad, [all laugh] but I’d say it was interesting but very fun. So I’m glad that I went along with it. I was very confused in the beginning about all the scans. There was one phase when my whole face was just little triangles. It was really fascinating to see the whole process from start to finish.

What was your favourite part of the process?

AC: Probably when I could do little details like my hair colour, the way my hair looked – that kind of the styling of it, the clothes I wore, because that was the part of it that I could actually understand, the whole system, but then of course also the little things where we complement each other, like “That needs to be fixed, I don’t know how to do it, but you know how to work this”. I enjoyed all those small, collaborative pieces.

Was there anything about the process or that made you feel weird or uncomfortable or that elicited some strong emotional reaction?

AC: I was really surprised by how it turned out.

JC: I remember you saying it was weird: when you saw the MetaHuman talking with your voice about art, you felt a bit weird.

AC: Yeah, it was weird because it was me, with my voice, how I talk, talking about something that I love, but I’m not used to seeing a digital version of myself.

Were these words that you had actually spoken, or were these generated after the AI was fed your voice?

AC: My dad recorded me on an iPad for about one minute, just talking about things that I like; it was random, it was not complete sentences, just to see if it could remake the way I talk. And then after a while we fiddled with it and used my voice and typed out words, but the first time [we tried it], it was me talking and then we implemented that [directly] into the AI version.

JC: The video is something you can generate with an Unreal Engine tool; you just scan your face, all of the muscles that you move when you talk, and then you export one file and that file can be imported into Unreal Engine and it’s going to make the MetaHuman’s face move just like the video. I extracted the audio – it was a one-to-one match. So the part of the audio that [wasn’t recorded, but was generated] is a lip sync. If we type something [new] and then we try to make Amanda’s face appear that they're saying that, if you’re not really paying attention, it looks okay; but if you pay attention, it’s gonna look weird: sometimes your mouth is kind of closed when you’re saying ‘ahh’, since [the tech] is pretty new. But I’m very confident that other AI models are gonna help solve a lot of problems, and this isn’t going to be an issue anymore – maybe in a few months.

Was it weird seeing the avatar say these things that you yourself didn’t say, Amanda?

AC: Well, in the beginning it was the words that I said. But it was interesting to see myself speaking and at the same time not speaking myself.

JC: Did you ever think that maybe, eventually at some point it’s gonna be so easy for people to own parts of your personality and then use them?

AC: I’ve thought about it, and there’s been a few cases where people have used people’s cloned voices to scam people for money, but I think that’s putting a bad overall [spin] on this, because it’s still a new thing – and people are looking at what it’s capable of but not really experimenting in what else it can do. And that’s not shining a lot of light on the possibilities that it can be used for good, but only on the negatives.

JC: I would agree with that – I think humans by nature have a resistance to change, or something new. I think AI gets (often with good reason) [a bad rap] – it’s easier to look at the bad side, but I think that there’s so much to be done there [for good]. And the question is, who’s gonna do it?

AI is not the Metaverse in terms of being a trend. This is not going away at all. Things are gonna happen whether you like it or not. So I’m hoping that more good things happen than not, like maybe having avatars of figures who are inspiring to kids. If a kid wants to be an astronaut, they could have a chat with Neil Armstrong and ask him lots of questions. They will definitely learn more this way as it's a lot more engaging [than traditional educational material].

AC: It’s also so new that only certain people have access to it, and those people aren’t really showing all sides of it. So for the people that don’t have access to it, they’re only seeing the negatives, and I think it’s interesting how easily we only focus on what is bad and not the good. If everyone had access to this it would be much easier for people to understand how it can help, but of course we need to know the downsides to this too.

JC: Do you think it’s easier for you, because you’re Gen Z, and you think it might be easier for you than a millennial, or my parents who are boomers, to grasp this big new piece of technology?

AC: Well I think it’s easier for me [than for my peers], because of course you’ve worked with this, I’ve always been around this environment, and not many people have that. So I've always had a good understanding of it.

Is all of this - questions about AI, these more theoretical questions and also the practical applications – something you and your friends talk about at all?

AC: I have very few friends that are into this kind of stuff. I have one friend who’s a big nerd, he loves everything knowledge-wise. One thing we do talk about at least for school sometimes is ChatGPT, which I think has helped a lot of us, but it’s also such a small aspect of the AI world. But if we’re talking about the MetaHuman, like mine, that sort of thing, I haven't talked about it with my friends, because I understand it to a certain extent, but if I don’t have all the information, I don’t want to explain it to them [in a way] that might leave a [negative or inaccurate impression of it].

So you didn’t talk to your friends about this project at all?

AC: I think just to one friend. “My dad’s just working on this little project.” [Juan laughs.] I think I’m very used to it by this point that it’s not a big deal for me.

There was one time I was going through my camera roll [on my phone], and I had a bunch of screenshots of when you [Dad] were sending pictures [of the project], and my friends were like, “What’s that?” I’m like, “Oh, that’s when my dad made a digital version of me” and I kept scrolling. They were like, [nonchalantly] “Huh, okay.”

They didn’t have any questions or strong reactions?! [Juan and Victoria laugh incredulously.]

AC: Not that I can remember, but it was just a project of my dad’s. [Juan laughs.] I knew they were a bit confused, but we were really tired, we just kept scrolling. But I think that’s the one time I had a reaction.

It’s interesting because I think if it were my friends they’d be like "Wait, what?" And then we’d chat about it.

You complement each other and worked so well on this project together. Did you learn anything about each other while you were doing this or become closer about certain things?

JC: I think that we’ve always been pretty close, so I don't really see that we gained anything in terms of getting closer, but it sparked some things. I was like, “Okay, Amanda is a teen, so isn’t that phase when they need to spend more time with friends, with their peers, and less time with parents?” And that's how it is, right? It’s not about me or how I feel. But it’s almost like a thought experiment – like, “Oh, I could have my Amanda forever and talk to them whenever I want”, and then I was like, “That’s messed up.”

How did both of you feel about the idea of consent while making Amanda’s avatar? What do you think some of the consent concerns and big issues are?

JC: I didn’t realise it was going to be a lot like you, so I felt the need to ask consent. “I’m doing this, can I publish it?” It feels kind of like posting something about you without asking you, even though it’s not you.

AC: I think always of course consent is key – that’s the phrase — but also just, as you said it’s so close to me, or anyone in general – this could be so close to them, that it’s publishing yourself, almost. Not everyone wants that. But also, at what point is someone eligible to give consent or in their right mind to give consent?

It seems like someone can make you say something or use you in a way that you didn’t consent to, even if you consented to make the avatar.

What are you doing with this project? Are you going to keep refining it? Are you gonna make another Amanda when they’re 18 and see how the technology will have evolved, how they will have evolved...

JC: Amanda, what do you think we should do with it?

AC: I don’t know, I think it’s an interesting project that I don’t think has been done by many people, and then again, people have been mainly focusing on the negatives of AI so if you can maybe show the positive, I think that would be great, but then obviously there’s gonna be people turning your work against you.

JC: I don’t know if I will do it with Amanda’s MetaHuman, but something that I want to do with time is fine-tune the model to be more like someone: feed it life stories, feed it personality traits, feed it the kind of humour, and then have them as a “human”, maybe in your phone, and be able to talk to it and it will answer back with the person’s actual voice. I think I would be curious to try that, because in my line of work, you can make assumptions about how something might feel or will make you feel – I have an idea of how this might make me feel – but I think after it’s done, I think that’s gonna be a lot different.

It could even be myself for Amanda in the future. You [Amanda] mentioned to me one time “Maybe, if sometimes I’m having a bad day, I’d like to hear your voice that things are okay” – and I think that’s the interesting part. I want to feed into the project - it doesn’t have to be your MetaHuman, it could be mine.

It’s the same process; I know it’s something that will take less than a week to finish, and then it’s just a matter of feeding more stories and personality traits into the model. It’s something that I’m planning to do and see how it feels – show it to some people, pay really close attention to how people react to it, I think that will be really interesting.I think it’s like the next step of our thought experiment.

There is so much untapped potential if you mix multiple AI services. Next step would be enabling Amanda to use a fine-tuned LLM [large language model] to be more like them, and use ElevenLabs API to get the avatar to say these AI-generated things with their voice.

Have you shown the project to anyone or put anything online about it? How private are you with it?

JC: I asked if you could put it on instagram, and I also used it for the presentation that we did at AWE [US in June], but I didn’t mention that it was my daughter – it was just providing assets for what I was talking about: MetaHumans in general, and how we used it for that specific project. For the very few people I talk to about it, it’s very 50/50 - people are like, “Wow!” and keep talking, or people are like, “That’s too weird for me”, so that’s why I’m being mindful [of how I share it].

Showing Amanda without saying it’s them is almost a way of not sharing them.

JC: And also my instagram is private.

Amanda, how do you feel about the fact that your dad showed your avatar at a conference?

AC: It was fun – my face was in a very well-known conference!

JC: Your actual face alongside a MetaHuman face.

AC: I’m practically famous. [all laugh]

Find out more about our perspectives on human-first AI.